Once again, another year has flown past and I find myself preparing for another deployment to the ice. As with years past, I've been having to go through the PQ (physical qualification) process to assure NSF that I am healthy enough to travel and stay there. This requires a full physical, a trip to the dentist (no one wants to get a toothache down there) and a full blood workup (so. much. blood.). Our tentative dates are to be on the ice beginning November 4th and return to the U.S. sometime during the first week in December.

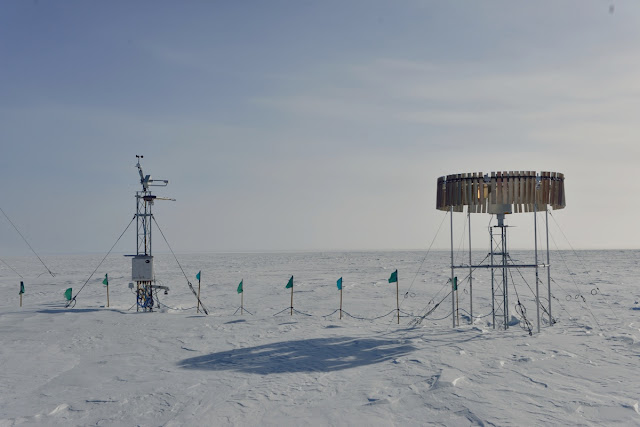

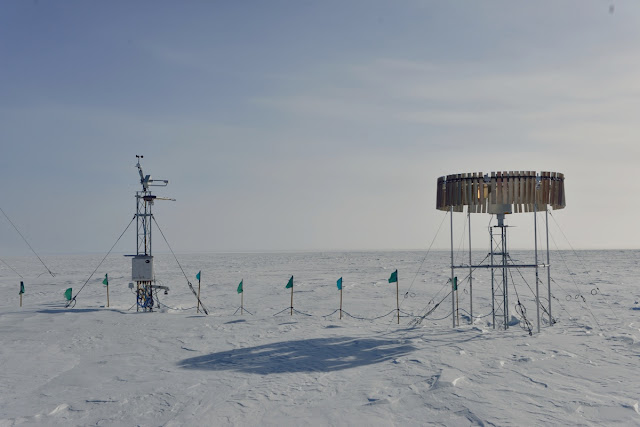

As you might have guessed from the title, this is the last year of my three-year grant and the purpose of our trip is to remove all of our equipment and have it shipped back to the United States. Under normal conditions elsewhere, this might be a week-long endeavor, but nothing is ever that easy in Antarctica. Typically the first week on the ice is spent in training, most of which will be a refresher, to make sure we are safe on the ice. That leaves roughly three weeks to get everything taken down. Still seem like a long time? You will recall from one of my blogs the first year that we installed everything on towers and that we buried the base of those towers in about three feet of snow to help stabilize them. Depending on the site, an additional one to two feet of snow can accumulate each year, meaning the towers could be buried in five to seven feet of snow and ice by now (see pics below). Not only do we have a lot of digging to do, we also have to contend with mother nature and competing priorities for other NSF projects on the aircraft and rotor craft we need to get us to the remote sites (Lorne and Tall Tower). Then there is the time to repack everything for the journey back north. Undoubtedly, those four weeks will fly by.

|

| Me standing next to one of the original gauge installations in 2017. Notice the height of the horizontal bars are nearly even with my head. |

|

| Photo of the same site last year (2018). The horizontal bars were even with the middle of my chest after just one year. (I'm the invisible guy on the left). |

With the conclusion of our field work, the question naturally is "so what did you learn?" Well, we learned a lot! We have learned that measuring precipitation is hard, but measuring sublimation (where ice converts directly to a vapor without melting) is harder. Precipitation events happen over the course of hours, sometimes days. Sublimation can happen over the course of days and weeks and at much lower rates than precipitation. Even so, we have found we can indeed measure sublimation rates and are working on finalizing some of that analysis for a publication later next year. We also learned we can indeed measure precipitation in Antarctica, even at temperatures down around -50 (and the equipment functioned at those temperatures with no problem). Lots of analysis continues on that as well. Can we distinguish blowing snow from falling snow? That we can't answer until we can collect the data from the particle size sensors that are archiving the data at each site (and can't transmit the data to us because it's too big). Thus, while we have a good data set thus far, there's still more to get and more analysis to do over the next year. There are lots of other things we learned (don't install a DFIR shield three feet or less above the snow surface, don't forget to put the radio on switched power instead of constant power, don't eat the brown snow near the seals, etc.) but the important ones are listed above.

I also realized I never had the chance to go back and post some of the pictures of my return flight off the ice last year, so here's a quick summary. Because we had finished things a bit early last year, I opted to leave a few days early to get back so I could prep for an FAA meeting that was scheduled immediately upon my return. I was hoping to get lucky and get the Boeing 757 aircraft on the way back, but alas, we had another 8-hour flight back on a C-130. Unlike the prior year though, this flight was much less crowded and it was much easier to move about the plane. I was even able to get some pictures out of the (very few) windows on the aircraft as we flew north back to Christchurch. I'll conclude this post with some of the photos from that return journey. My next post will likely be in late October as we prepare for our last trip down to the ice.

|

| Standing in line to board the C-130 for the journey back north. | | | | | |

|

| Once on board the aircraft, everyone scopes out their seat while cargo is still being loaded on the back end. |

|

| Before takeoff, the crew gives a quick briefing on what to do during an emergency. Air sick bags are plentiful and hung in many obvious locations above the seats. (Thankfully, no one used any). |

|

|

|

| The infamous Elaine Hood poses for a picture while enjoying the plethora of space around her. |

|

|

| Here's a unique use for Big Red. Want to get some shut-eye on the flight but it's too bright to sleep? Simply weave the hood on Big Red through the meshing and drape the lower portion of the coat around you like a teepee. Clearly, Elaine has learned some tricks over the years. |

|

| Um, can someone tell the pilot the propeller is bent? (Actually the slow shutter speed on my phone meant the propeller motion blurred a bit). Below the plane is some of the annual sea ice in the process of breaking up for the summer. | |

|

| The sun glints off the ocean through cracks in the sea ice. |

|

| A closer view of the patchwork of sea ice floating on the ocean. |

|

| Arrival in Christchurch! My first view of liquid water in a month. |

|

| Penguins!!! Ok, so I cheated a bit here. These Blue Penguins can be found at the International Antarctic Center in Christchurch, located next to the airport. While waiting for my afternoon flight, I wandered over to the center (people who travel to/from Antarctica get free admission) and found these guys inside. They are New Zealand's smallest penguins and have been taken in because of injuries they sustained from cars, people, dogs and other pests. They aren't endangered but are considered "at risk" due to their declining numbers in the wild. |

Comments

Post a Comment